ORM Leaking More Than You Joined For

Developers are still exposing ORMs through robust filtering and search functionality.

Developers are still exposing ORMs through robust filtering and search functionality.

In this article, we expand on our previous Object Relational Mapper (ORM) Leak research and Black Hat EU briefing by showcasing an interesting expression‑parser bug in the Beego ORM that we used to bypass ORM Leak protections in Harbor. We also demonstrate an authentication‑bypass technique for the Prisma ORM that was omitted from our original Prisma article.

We further argue that the introduction of an ORM Leak vulnerability does not depend on the use of a susceptible ORM such as Django or Prisma. Developers frequently implement robust filtering capabilities that parse user input into filter expressions for the underlying ORM of their choice, yet it is commonly overlooked that filtering on sensitive attributes should be disallowed.

To demonstrate this, we show how Microsoft’s OData API can unintentionally expose sensitive attributes and Entity Framework filtering functionality. This behaviour was abused during a project earlier this year, where we were also able to bypass naive protections intended to prevent filtering of sensitive data.

We have also published semgrep rules for detecting potentially dangerous uses of the Django, Prisma, Beego, and Entity Framework ORMs at https://github.com/elttam/semgrep-rules.

In this article, we introduced the ORM Leak vulnerability class and demonstrated vulnerable uses of the Django ORM that allowed filtering on sensitive fields. We showcased a variety of exploitation techniques, including many-to-many relational filtering payloads that pivot through relationships to reach sensitive fields on connected objects. We also highlighted that response length differences are not the only viable oracle for ORM Leak attacks, showing how ReDoS payloads on a MySQL database can be used to perform error-based attacks.

plORMbing your Prisma ORM with Time-based Attacks

This article demonstrated that the Prisma ORM is also susceptible to similar relational filtering attacks to those showcased in our Django article, when developers allow users to control the where option, albeit with a different filtering syntax. Since Prisma provides greater control over the generated SQL queries compared to Django, we explored time-based attacks, which led to the development of plormber, a tool for exploiting time-based ORM Leak vulnerabilities.

Beego is one of the most popular Golang web frameworks (over 32k GitHub stars). Its filtering syntax is heavily inspired by the Django ORM, as shown in the example below.

o := orm.NewOrm()

search := c.Ctx.Input.Query("search")

qs := o.QueryTable("articles")

qs = qs.Filter("title__contains", search)

var articles []*Article

_, err := qs.All(&articles)

Similarly, the Beego ORM adopts the same convention as Django for relational filtering.

qs.Filter("created_by__user__username__contains", search)

As a result, an ORM Leak vulnerability can be easily introduced when using the Beego ORM if a developer allows a user to control the filter expression parameter for the Filter function.

qs.Filter(filter_expression, filter_value) <1>

<1> Vulnerable to ORM leaks if the user controls the filter_expression parameter.

All the ORM Leak attacks discussed in our plORMbing your Django ORM blog article also apply to the Beego ORM. For this reason, we initially chose not to publish our findings that Beego was similarly susceptible.

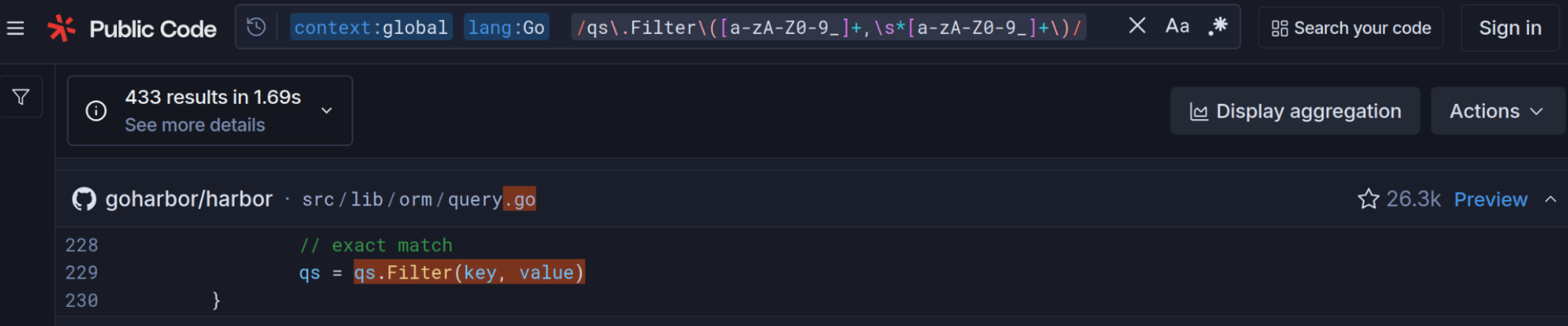

However, earlier this year we decided to see how quickly we could discover an ORM Leak vulnerability in a large open-source project, and we came across this code snippet in Harbor in under 20 minutes.

Harbor is a popular open‑source container registry (over 27k GitHub stars) built using the Beego web framework, and it relies on the Beego ORM for managing application data. The snippet above was located in the setFilters function shown below. This function was used to parse the q URL parameter for all List API handler endpoints.

setFilters function in goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.12.2/src/lib/orm/query.go

// set filters according to the query

func setFilters(ctx context.Context, qs orm.QuerySeter, query *q.Query, meta *metadata) orm.QuerySeter {

for key, value := range query.Keywords {

// The "strings.SplitN()" here is a workaround for the incorrect usage of query which should be avoided

// e.g. use the query with the knowledge of underlying ORM implementation, the "OrList" should be used instead:

// https://github.com/goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.2.0/src/controller/project/controller.go#L348

k := strings.SplitN(key, orm.ExprSep, 2)[0]

mk, filterable := meta.Filterable(k)

if !filterable {

// This is a workaround for the unsuitable usage of query, the keyword format for field and method should be consistent

// e.g. "ArtifactDigest" or the snake case format "artifact_digest" should be used instead:

// https://github.com/goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.2.0/src/controller/blob/controller.go#L233

mk, filterable = meta.Filterable(snakeCase(k))

if !filterable {

continue

}

}

// filter function defined, use it directly

if mk.FilterFunc != nil {

qs = mk.FilterFunc(ctx, qs, key, value)

continue

}

// fuzzy match

if f, ok := value.(*q.FuzzyMatchValue); ok {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__icontains", Escape(f.Value))

continue

}

// range

if r, ok := value.(*q.Range); ok {

if r.Min != nil {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__gte", r.Min)

}

if r.Max != nil {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__lte", r.Max)

}

continue

}

// or list

if ol, ok := value.(*q.OrList); ok {

if ol == nil || len(ol.Values) == 0 {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__in", nil)

} else {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__in", ol.Values...)

}

continue

}

// and list

if _, ok := value.(*q.AndList); ok {

// do nothing as and list needs to be handled by the logic of DAO

continue

}

// exact match

qs = qs.Filter(key, value) <1>

}

return qs

}

<1> The ORM Leak sink that was identified by searching for the qs.Filter\([a-zA-Z0-9_]*,\s*[a-zA-Z0-9_]*\) pattern on Sourcegraph.

For example, the q URL parameter for GET /api/v2.0/users?q=email=~elttam.com would be parsed as the email__icontains filter expression for the Beego ORM, returning all users whose email addresses contain elttam.com. However, there were no protections to prevent users from filtering on sensitive attributes such as password or salt.

Oddly, Harbor did not use the relational features of the ORM and instead relied on custom SQL for applying table joins in specific cases. This inadvertently reduced the exploitability of the ORM Leak vulnerability, as we could not use relational filtering techniques on endpoints accessible to low‑privileged or unauthenticated users. Exploitation required sufficient permissions to list other users.

This basic ORM Leak pattern is a common mistake we observe during engagements: an endpoint parses a user‑controllable filter constraint for querying users without preventing filtering on sensitive attributes.

What made this specific vulnerability in Harbor particularly interesting—and worth publishing—was our ability to repeatedly bypass Harbor’s patches due to how the Beego ORM parses filter expressions in its Filter method.

In Harbor version v2.13.0, the parseFilterable validation function was introduced to set the Filterable attribute of a model field to true if the field does not have the filter annotation set to false when parsing a data model, and to false otherwise. Sensitive model fields were then annotated with filter:"false", as shown in the following snippet from the User data model.

type User struct {

...

Password string `orm:"column(password)" filter:"false" json:"password"`

...

Salt string `orm:"column(salt)" filter:"false" json:"-"`

...

}

The Filterable attribute was then validated when parsing the user-controlled q parameter in setFilters (shown below). If it was false, the corresponding filter constraint was removed.

setFilters function in goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.13.0/src/lib/orm/query.go

// set filters according to the query

func setFilters(ctx context.Context, qs orm.QuerySeter, query *q.Query, meta *metadata) orm.QuerySeter {

for key, value := range query.Keywords {

// The "strings.SplitN()" here is a workaround for the incorrect usage of query which should be avoided

// e.g. use the query with the knowledge of underlying ORM implementation, the "OrList" should be used instead:

// https://github.com/goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.2.0/src/controller/project/controller.go#L348

k := strings.SplitN(key, orm.ExprSep, 2)[0] <1>

mk, filterable := meta.Filterable(k) <2>

if !filterable {

// This is a workaround for the unsuitable usage of query, the keyword format for field and method should be consistent

// e.g. "ArtifactDigest" or the snake case format "artifact_digest" should be used instead:

// https://github.com/goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.2.0/src/controller/blob/controller.go#L233

mk, filterable = meta.Filterable(snakeCase(k))

if mk == nil || !filterable {

continue

}

}

...

// exact match

qs = qs.Filter(key, value) <3>

}

return qs

}

<1> Splits the user controllable filter expression and retrieves the first section as the filter key.

<2> Validates if the filter key was filterable.

<3> ORM Leak sink.

Note that Harbor only validated the start of the filter expression, so if Harbor did utilise the relational features of the Beego ORM, this protection could have been easily bypassed using relational filters. However, we were not afforded that luxury.

We did, however, notice an interesting quirk in how the Beego ORM parses non-relational fields within a filter expression via the parseExprs function. The filter expression is first split by the __ expression section separator, and the parseExprs function then iterates over each segment in a loop. If a non-relational field is used as though it were a relational field—such as email in the email__password filter expression—it is overwritten by the subsequent field in the expression.

In practice, this means the filter expression email__password__startswith is equivalent to password__startswith when using the Beego ORM, which conveniently bypasses Harbor’s deny-list patch.

The second patch Harbor implemented in v2.13.1-rc1 restricted the filter expression in the q input to allow only a single use of the Beego expression separator (__). The intention was to still allow users to choose a Beego operator for filtering fields, while preventing the email__password__startswith bypass described in the previous section.

goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.13.1-rc1/src/lib/orm/query.go

// set filters according to the query

func setFilters(ctx context.Context, qs orm.QuerySeter, query *q.Query, meta *metadata) orm.QuerySeter {

for key, value := range query.Keywords {

// The "strings.SplitN()" here is a workaround for the incorrect usage of query which should be avoided

// e.g. use the query with the knowledge of underlying ORM implementation, the "OrList" should be used instead:

// https://github.com/goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.2.0/src/controller/project/controller.go#L348

keyPieces := strings.Split(key, orm.ExprSep)

if len(keyPieces) > 2 { <1>

log.Warningf("The separator '%s' is not valid in the query parameter '%s__%s'. Please use the correct field name.", orm.ExprSep, keyPieces[0], keyPieces[1])

continue

}

...

<1> Only allows one occurrence __ in the filter expression.

The issue with this patch is that Harbor maintains its own mapping to Beego operators based on the format of the value.

The Build function in goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.13.1-rc1/src/lib/q/builder.go

// Build query sting, sort and pagination information into the Query model

// query string format: q=k=v,k=~v,k=[min~max],k={v1 v2 v3},k=(v1 v2 v3)

// exact match: k=v

// fuzzy match: k=~v <1>

// range: k=[min~max]

// or list: k={v1 v2 v3}

// and list: k=(v1 v2 v3)

// sort format: sort=k1,-k2

func Build(q, sort string, pageNumber, pageSize int64) (*Query, error) {

keywords, err := parseKeywords(q)

...

return &Query{

Keywords: keywords,

...

}, nil

}

<1> The fuzzy match Harbor query format.

Fuzzy match mapping to __icontains operator in goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.13.1-rc1/src/lib/orm/query.go

func setFilters(ctx context.Context, qs orm.QuerySeter, query *q.Query, meta *metadata) orm.QuerySeter {

for key, value := range query.Keywords {

...

// fuzzy match

if f, ok := value.(*q.FuzzyMatchValue); ok {

qs = qs.Filter(key+"__icontains", Escape(f.Value)) <1>

continue

}

...

<1> Inserts the insensitive contains (__icontains) operator if the query value is a fuzzy match.

Using this, Harbor’s second patch was bypassed by leveraging the fuzzy match value format with the email__password filter expression. However, the case sensitivity of the salt field was lost due to the use of the __icontains Beego operator.

In Harbor version v2.14.0, the ORM Leak vulnerability was finally patched by validating the second section of a filter expression against a set of allowed Beego operators. This effectively validates the entire filter expression input and prevents payloads such as email__password=~.

The operator allow list check within setFilters in goharbor/harbor/blob/v2.14.0/src/lib/orm/query.go

// only accept the below operators

if len(keyPieces) == 2 {

operator := orm.ExprSep + keyPieces[1]

allowedOperators := map[string]struct{}{

"__icontains": {},

"__in": {},

"__gte": {},

"__lte": {},

"__gt": {},

"__lt": {},

"__exact": {},

}

if _, ok := allowedOperators[operator]; !ok {

log.Warningf("the operator '%s' in query parameter '%s' is not supported, the query will be skipped.", operator, key)

continue

}

}

There are three key takeaways from the ORM Leak vulnerability we discovered in Harbor:

Robust Filtering Capabilities

One root cause of this vulnerability was that the Harbor API allowed user inputs to set both the field and operator for filtering users, without validating against sensitive fields.

This type of issue is very common in our engagements, even on targets under bug bounty programs. Basic ORM Leak vulnerabilities appear more frequently than similar classes like SQL injection.

The Beego ORM Filter Expression Parsing is Broken

The broken parsing in the parseExprs function can be exploited to bypass naive ORM Leak protections that do not validate the entire filter expression containing user-controlled sections.

We reported this parsing issue to the Beego contributors in May 2025, but did not receive an adequate response. The issue is still present in the latest version (v2.3.8) at the time of this article.

This is not the first filter expression parsing bug discovered that could bypass ORM Leak protections. For example, Strapi - CVE-2023-34235 allowed insertion of a WHERE SQL condition with a field that did not exist on the corresponding model, bypassing Strapi’s patch for CVE-2023-22894.

Application Mappings to ORM Operators

Developers often implement mappings from user input to ORM operators, which can inadvertently introduce ORM Leak vulnerabilities.

During another engagement, we observed this with the Sequelize ORM, which uses a syntax similar to Prisma ORM. While Sequelize itself is generally resistant to ORM Leaks because its operators are JavaScript Symbol types, a middleware in the application we were testing mapped string inputs to Sequelize operators, resulting in an ORM Leak vulnerability.

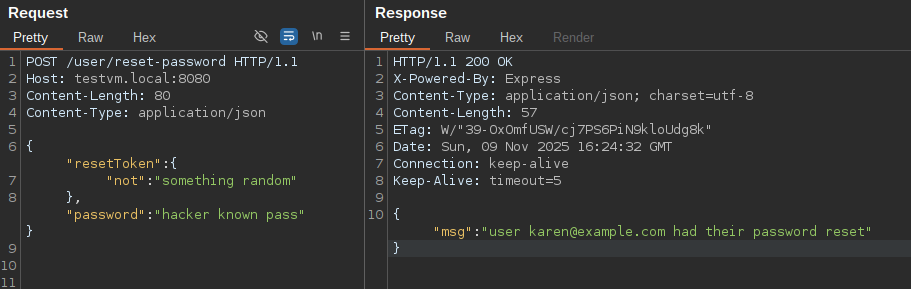

In our original Prisma ORM Leak article, we overlooked including a common mistake that we have observed: assuming the type of a user input when filtering by a field.

For example, the following TypeScript snippet shows a password reset endpoint in an ExpressJS application that resets the password for the first user where the resetToken field is equal to the provided resetToken input.

const app = express();

app.use(express.json())

app.post('/user/reset-password', async (req, res) => {

if ((req.body.resetToken ?? "") === "") {

res.status(400).json({"msg": "invalid code"})

return

}

try {

const user = await prisma.user.findFirstOrThrow({

where: {

resetToken: req.body.resetToken as string <1>

}

})

await prisma.user.update({

where: {id: user.id},

data: {password: req.body.password, resetToken: null}

})

res.json({"msg": `user ${user.email} had their password reset`})

} catch (error) {

console.error(error)

res.status(400).json({"msg": "invalid code"})

}

})

<1> Assumption that the resetToken input is a string type.

Ignoring the insecure non-constant time comparison when comparing a sensitive value within a database query, there is an implicit assumption that the user input is of type string and that a simple equality comparison will be performed. However, as mentioned previously, the Prisma ORM uses an object-based syntax, where operators are defined using objects.

In this case the resetToken value in the JSON request can be manipulated into an object that injects a Prisma operator. In the following example, this bypasses the reset token validation by injecting the not condition, which is conceptually similar to NoSQL injection.

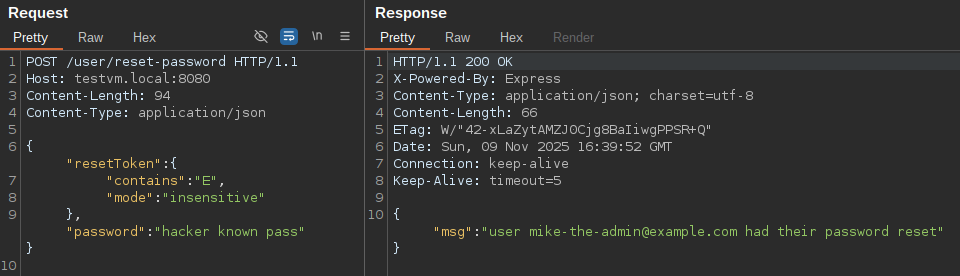

Another useful operator for bypassing authentication checks in Prisma is contains, particularly when you want to avoid compromising the first user in the users table.

JSON request bodies are not the only way to coerce user input into an object type in ExpressJS (one of the most common frameworks we see used with Prisma).

For URL-encoded request bodies, if the extended option is enabled for the middleware (app.use(express.urlencoded({ extended: true }))), an input such as resetToken[not]=E is parsed into the object {"resetToken": {"not": "E"}}, injecting the not condition.

Similarly, prior to ExpressJS version 5.x, URL parameters were parsed using the extended parser by default, allowing inputs like resetToken[not]=E to be coerced into objects. While the default URL parameter parser was changed to the “simple” parser in ExpressJS 5.x, we still commonly observe the extended parser enabled in ExpressJS 5.x applications.

Another commonly overlooked input vector is cookies. If the ExpressJS cookie-parser middleware is enabled, it supports JSON Cookies, which parse cookie values prefixed with j: using JSON.parse. A header such as Cookie: resetToken=j:{"not": "E"} would result in the resetToken cookie being parsed into an object, injecting the not condition when used in a Prisma filter.

In summary, when input type validation is missing and the Prisma ORM is used, the resulting impact can be severe.

As mentioned in the key takeaways section on the Beego ORM, one point we want to clarify for software engineers and security testers is that the introduction of an ORM Leak vulnerability does not depend on using a susceptible ORM such as Django, Prisma, or Beego.

The most common root cause we observe is the growing trend for web applications to offer robust filtering or search capabilities, which can be abused to filter objects by sensitive or hidden fields. Developers often rely on the ORM to determine which fields are queryable and to prevent SQL injection, but overlook explicitly validating which fields should be queryable.

A good example of this issue arises with robust filtering features in applications using the Entity Framework ORM, which we consider not inherently susceptible to ORM Leaks. Introducing an ORM Leak using Entity Framework typically requires additional custom parsing logic for a user input. By contrast, demonstrating ORM Leaks with Django, Beego, or Prisma often requires only a single line of code.

To illustrate the code required to introduce an ORM Leak vulnerability in Entity Framework, the following snippet is taken from Microsoft’s documentation on LINQ expressions and constructing runtime queries. This pattern would be vulnerable to ORM Leaks if the source Entity Framework model contained a sensitive field of type string and an attacker could control the search term.

Microsoft - Query based on run-time state

// using static System.Linq.Expressions.Expression;

IQueryable<T> TextFilter<T>(IQueryable<T> source, string term)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(term)) { return source; }

// T is a compile-time placeholder for the element type of the query.

Type elementType = typeof(T);

// Get all the string properties on this specific type.

PropertyInfo[] stringProperties = elementType

.GetProperties()

.Where(x => x.PropertyType == typeof(string)) <1>

.ToArray();

if (!stringProperties.Any()) { return source; }

// Get the right overload of String.Contains

MethodInfo containsMethod = typeof(string).GetMethod("Contains", [typeof(string)])!;

// Create a parameter for the expression tree:

// the 'x' in 'x => x.PropertyName.Contains("term")'

// The type of this parameter is the query's element type

ParameterExpression prm = Parameter(elementType);

// Map each property to an expression tree node

IEnumerable<Expression> expressions = stringProperties

.Select(prp =>

// For each property, we have to construct an expression tree node like x.PropertyName.Contains("term")

Call( // .Contains(...)

Property( // .PropertyName

prm, // x

prp

),

containsMethod,

Constant(term) // "term" <2>

)

);

// Combine all the resultant expression nodes using ||

Expression body = expressions

.Aggregate((prev, current) => Or(prev, current));

// Wrap the expression body in a compile-time-typed lambda expression

Expression<Func<T, bool>> lambda = Lambda<Func<T, bool>>(body, prm);

// Because the lambda is compile-time-typed (albeit with a generic parameter), we can use it with the Where method

return source.Where(lambda);

}

<1> Includes all properties of the given T data model that are a string type, which could contain sensitive fields.

<2> Will also search by the value of sensitive fields.

Generated SQL that filtered sensitive string fields using the user controllable term input.

info: Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Database.Command[20101]

Executed DbCommand (3ms) [Parameters=[@__p_0='?' (DbType = Int32), @__p_1='?' (DbType = Int32)], CommandType='Text', CommandTimeout='30']

SELECT [u].[Id], [u].[Username]

FROM [Users] AS [u]

WHERE [u].[Username] LIKE N'%attackerinput%' OR [u].[Password] LIKE N'%attackerinput%' OR [u].[ApiToken] LIKE N'%attackerinput%'

ORDER BY [u].[Username]

OFFSET @__p_0 ROWS FETCH NEXT @__p_1 ROWS ONLY

It is a common mistake in web applications for utility search functions to inadvertently filter on sensitive fields within a data model.

Directus CVE-2025-64748, published last month, is a good example of this issue. In this case, the application included the token and tfa_secret fields when searching objects in the directus_users collection, as shown in the generated SQL from Directus.

select `directus_users`.`token`, `directus_users`.`id` from `directus_users` where (

...

LOWER(`directus_users`.`tfa_secret`) LIKE ? or

...

LOWER(`directus_users`.`token`) LIKE ? or

...

) order by `directus_users`.`id` asc limit ?

There are also libraries that add advanced filtering capabilities to API endpoints by integrating with an underlying ORM, which can inadvertently introduce ORM Leak vulnerabilities.

Ransacking your password reset tokens is an excellent article by Lukas Euler describing how the Ransack library for ActiveRecord allowed filtering on all model attributes by default.

Another library we encountered during an engagement earlier this year that did not enforce an allow list for queryable fields was Microsoft’s ASP.NET OData Web API.

OData is a protocol for RESTful APIs that was first released in 2007 and standardises CRUD operations and filter syntax.

Security issues affecting OData APIs have been well known for over a decade, which is why we want to focus specifically, from a development perspective, on how sensitive fields can be inadvertently exposed in an ASP.NET OData API. We also discuss techniques we used during an engagement this year to bypass protections that did not follow best practices.

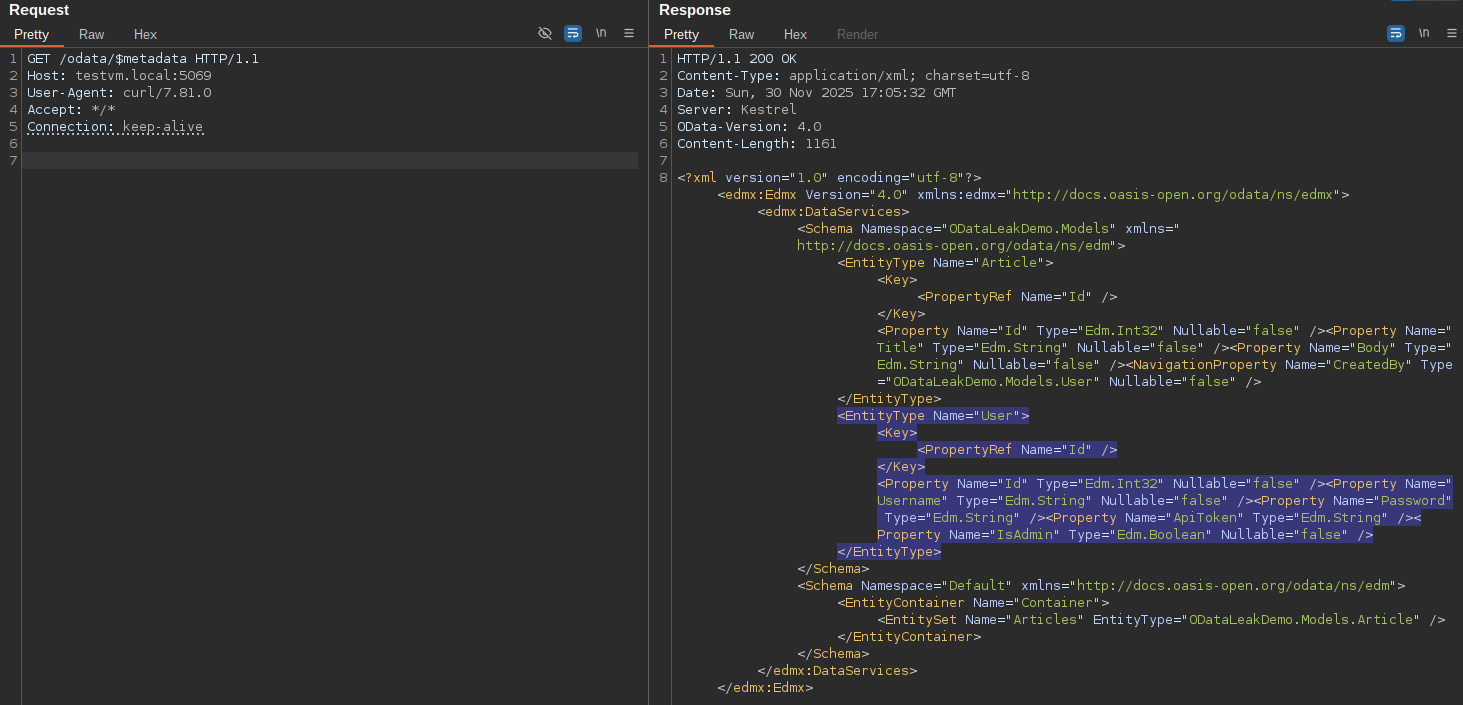

The OData standard defines the Entity Data Model (EDM) as an abstract metadata model that describes entity types, their properties, and their associations with other entity types exposed by OData API endpoints.

For example, in the following Article and User models, the Article model has an association to a User object via the CreatedBy field.

public class Article

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Body { get; set; }

public User CreatedBy { get; set; }

}

public class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public required string Username { get; set; }

public required string Password { get ; set; }

public string? ApiToken {get ; set; } // hex string

public bool IsAdmin { get; set; }

}

Adding data models to the EDM is done using the ODataConventionModelBuilder class. In the following snippet, it is important to note that only the Article model was explicitly included.

var modelBuilder = new ODataConventionModelBuilder();

modelBuilder.EntitySet<Article>("Articles");

The EDM can then be retrieved from the /$metadata endpoint. In our example application, the User model was automatically included in the EDM due to its association with the Article model, even though it was not explicitly added.

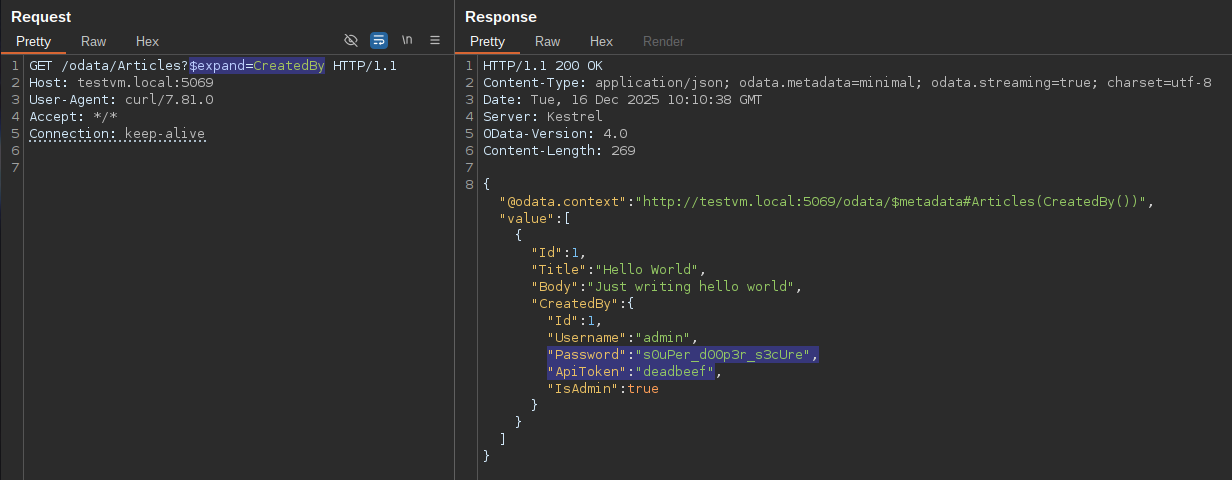

This is a common issue with OData APIs, where sensitive fields can be inadvertently included in the EDM and potentially exposed via an OData query endpoint using the $expand option.

OData controller for the Articles that has an OData query endpoint

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.OData.Query;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.OData.Routing.Controllers;

using ODataLeakDemo.Models;

namespace ODataLeakDemo.Controllers

{

public class ArticlesController : ODataController

{

private readonly DataContext ctx;

public ArticlesController(DataContext ctx)

{

this.ctx = ctx;

}

[EnableQuery] <1>

public ActionResult<IQueryable<Article>> Get()

{

return Ok(ctx.Articles); <2>

}

}

}

<1> Enables OData query options.

<2> The OData API parses user inputs into a LINQ expression that is then applied to the returned IQueryable<T>, which in this case are the Article objects from EntityFramework.

Using the $expand option to leak the CreatedBy association.

The best practice for sensitive fields is to exclude the field from the EDM using the IgnoreDataMember annotation.

However, this is a deny list approach that could result in the developer not adding the IgnoreDataMember annotation for a sensitive field or the developer not being aware of the IgnoreDataMember annotation, which is what we observed during an engagement.

In that engagement, the developer used the following protections to mitigate against the leaking of sensitive fields:

$filter option.startswith and contains) to prevent search operations on those fields.To replicate these protections, we just added the AllowedQueryOptions = AllowedQueryOptions.Filter and AllowedFunctions = AllowedFunctions.None options to our OData query endpoint in a demo application, as shown below:

[EnableQuery(

AllowedQueryOptions = AllowedQueryOptions.Filter,

AllowedFunctions = AllowedFunctions.None

)]

public ActionResult<IQueryable<Article>> Get()

{

return Ok(ctx.Articles);

}

The first protection was easily bypassed, as we could still write OData filter expressions on sensitive fields as part of an ORM Leak attack. However, the startswith and contains functions remained disabled.

To work around this, we used logical operators that were not disabled to perform comparisons based on the database collation (discussed in the next section) between a sensitive field and a string we controlled, allowing us to leak the full value.

Logical Operators Are Commonly Overlooked as a Search Mechanism

Logical operators such as greater than (>, gt, etc.) and less than (<, lt, etc.) can be used in ORM Leak attacks, yet are often overlooked by developers as a means of searching sensitive field values. We have used logical operators on multiple occasions to successfully exploit ORM Leak vulnerabilities.

Any ORM Could Be Leaked

With Entity Framework, we have shown that introducing an ORM Leak vulnerability typically requires more code than with more susceptible ORMs. However, this does not prevent developers from implementing filtering input parsers that can be abused to query the values of sensitive fields.

One concept we have omitted from our ORM Leak articles for the sake of simplicity is database collation, which defines the rules a database uses to store and compare data. Database collation can significantly impact the exploitation of ORM Leak vulnerabilities. For example, losing case-sensitivity due to the use of a case-insensitive collation, where the following databases use a case-insensitive collation by default:

Additionally, some ORMs attempt to handle case sensitivity at the application layer rather than relying on the database collation (e.g., Django and Beego), while others defer entirely to the database collation (e.g., Prisma and Entity Framework). Even then, ORMs that attempt to enforce case sensitivity may fail for certain database backends.

Louis Nyffenegger from PentesterLab provides a good example of this with Django and SQLite. In this case, the Django ORM loses case sensitivity for SQLite databases when using the __startswith or similar operators because the LIKE SQL condition in sqlite3 is case-insensitive. In contrast, the __regex operator preserves case sensitivity.

Another complication is that byte ordering in the database may not align with raw byte values due to collation rules, which are primarily designed to support different languages and character sets with varying sort orders. For example, using the default SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS collation in MSSQL, sorting a string produces results that are not ordered by byte value (as shown below). This directly affects logical operator based ORM Leak attacks, which rely on predictable ordering.

String of characters that were sorted by ascending byte order using latin1 encoding.

!"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

Getting the actual character ordering of the default SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS collation

1> DECLARE @input_string NVARCHAR(MAX) = ' !"#$%&''()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~';

2>

3> WITH SortedChars AS (

4> SELECT SUBSTRING(@input_string, number, 1) AS Char

5> FROM master.dbo.spt_values

6> WHERE type = 'P' AND number <= LEN(@input_string)

7> )

8> SELECT STRING_AGG(Char, '') WITHIN GROUP (ORDER BY Char COLLATE DATABASE_DEFAULT) AS SortedString

9> FROM SortedChars;

10> GO

SortedString

'-!"#$%&()*,./:;?@[\]^_`{|}~+<=>0123456789AabBCcdDEefFGghHIijJKklLMmnNOopPQqrRSstTUuvVWwxXYyzZ <1>

(1 row affected)

<1> Symbols are treated as special characters that have a lower sort value than alphanumeric characters when using the SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS collation.

Using the SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS sorted string in a logical operator ORM Leaks attack.

Below is a list of SQL collations, along with example queries for sorting characters and their corresponding outputs, to help readers determine character ordering for some of the most popular databases and collations:

MSSQL

Default collation:

1> SELECT CONVERT (varchar(256), SERVERPROPERTY('collation'));

2> GO

SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS

(1 row affected)

DECLARE @input_string NVARCHAR(MAX) = '!"#$%&''()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~';

WITH SortedChars AS (

SELECT SUBSTRING(@input_string, number, 1) AS Char

FROM master.dbo.spt_values

WHERE type = 'P' AND number <= LEN(@input_string)

)

SELECT STRING_AGG(Char, '') WITHIN GROUP (ORDER BY Char COLLATE SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS) AS SortedString

FROM SortedChars;

Output for the above SQL.

SortedString

'-!"#$%&()*,./:;?@[\]^_`{|}~+<=>0123456789AabBCcdDEefFGghHIijJKklLMmnNOopPQqrRSstTUuvVWwxXYyzZ

MySQL and MariaDB

Default collations:

MySQL

mysql> SHOW COLLATION WHERE `Default` = 'Yes';

+---------------------+----------+-----+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

| Collation | Charset | Id | Default | Compiled | Sortlen | Pad_attribute |

+---------------------+----------+-----+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

| armscii8_general_ci | armscii8 | 32 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| ascii_general_ci | ascii | 11 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| big5_chinese_ci | big5 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| binary | binary | 63 | Yes | Yes | 1 | NO PAD |

| cp1250_general_ci | cp1250 | 26 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1251_general_ci | cp1251 | 51 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1256_general_ci | cp1256 | 57 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1257_general_ci | cp1257 | 59 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp850_general_ci | cp850 | 4 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp852_general_ci | cp852 | 40 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp866_general_ci | cp866 | 36 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp932_japanese_ci | cp932 | 95 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| dec8_swedish_ci | dec8 | 3 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| eucjpms_japanese_ci | eucjpms | 97 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| euckr_korean_ci | euckr | 19 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| gb18030_chinese_ci | gb18030 | 248 | Yes | Yes | 2 | PAD SPACE |

| gb2312_chinese_ci | gb2312 | 24 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| gbk_chinese_ci | gbk | 28 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| geostd8_general_ci | geostd8 | 92 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| greek_general_ci | greek | 25 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| hebrew_general_ci | hebrew | 16 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| hp8_english_ci | hp8 | 6 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| keybcs2_general_ci | keybcs2 | 37 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| koi8r_general_ci | koi8r | 7 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| koi8u_general_ci | koi8u | 22 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin1_swedish_ci | latin1 | 8 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin2_general_ci | latin2 | 9 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin5_turkish_ci | latin5 | 30 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin7_general_ci | latin7 | 41 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| macce_general_ci | macce | 38 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| macroman_general_ci | macroman | 39 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| sjis_japanese_ci | sjis | 13 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| swe7_swedish_ci | swe7 | 10 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| tis620_thai_ci | tis620 | 18 | Yes | Yes | 4 | PAD SPACE |

| ucs2_general_ci | ucs2 | 35 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| ujis_japanese_ci | ujis | 12 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf16le_general_ci | utf16le | 56 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf16_general_ci | utf16 | 54 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf32_general_ci | utf32 | 60 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf8mb3_general_ci | utf8mb3 | 33 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci | utf8mb4 | 255 | Yes | Yes | 0 | NO PAD |

+---------------------+----------+-----+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

41 rows in set (0.00 sec)

MariaDB

mysql> SHOW COLLATION WHERE `Default` = 'Yes';

+---------------------+----------+------+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

| Collation | Charset | Id | Default | Compiled | Sortlen | Pad_attribute |

+---------------------+----------+------+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

| big5_chinese_ci | big5 | 1 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| dec8_swedish_ci | dec8 | 3 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp850_general_ci | cp850 | 4 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| hp8_english_ci | hp8 | 6 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| koi8r_general_ci | koi8r | 7 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin1_swedish_ci | latin1 | 8 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin2_general_ci | latin2 | 9 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| swe7_swedish_ci | swe7 | 10 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| ascii_general_ci | ascii | 11 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| ujis_japanese_ci | ujis | 12 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| sjis_japanese_ci | sjis | 13 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| hebrew_general_ci | hebrew | 16 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| tis620_thai_ci | tis620 | 18 | Yes | Yes | 4 | PAD SPACE |

| euckr_korean_ci | euckr | 19 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| koi8u_general_ci | koi8u | 22 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| gb2312_chinese_ci | gb2312 | 24 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| greek_general_ci | greek | 25 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1250_general_ci | cp1250 | 26 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| gbk_chinese_ci | gbk | 28 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin5_turkish_ci | latin5 | 30 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| armscii8_general_ci | armscii8 | 32 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp866_general_ci | cp866 | 36 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| keybcs2_general_ci | keybcs2 | 37 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| macce_general_ci | macce | 38 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| macroman_general_ci | macroman | 39 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp852_general_ci | cp852 | 40 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| latin7_general_ci | latin7 | 41 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1251_general_ci | cp1251 | 51 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| utf16le_general_ci | utf16le | 56 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1256_general_ci | cp1256 | 57 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp1257_general_ci | cp1257 | 59 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| binary | binary | 63 | Yes | Yes | 1 | NO PAD |

| geostd8_general_ci | geostd8 | 92 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| cp932_japanese_ci | cp932 | 95 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

| eucjpms_japanese_ci | eucjpms | 97 | Yes | Yes | 1 | PAD SPACE |

+---------------------+----------+------+---------+----------+---------+---------------+

35 rows in set (0.00 sec)

DELIMITER $$

DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS sort_letters$$

CREATE PROCEDURE sort_letters()

BEGIN

DECLARE done INT DEFAULT 0;

DECLARE word VARCHAR(256);

DECLARE cur1 CURSOR FOR SELECT i FROM charslist;

DECLARE CONTINUE HANDLER FOR NOT FOUND SET done = 1;

DROP TEMPORARY TABLE IF EXISTS charslist;

CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE charslist (i VARCHAR(256));

INSERT INTO charslist VALUES ('!"#$%&''()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~');

DROP TEMPORARY TABLE IF EXISTS temp;

CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE temp (id INT, letter CHAR);

SET @wordcount = 0;

OPEN cur1;

REPEAT

FETCH cur1 INTO word;

IF NOT done THEN

SET @counter = 0;

SET @len = LENGTH(word);

WHILE (@counter <= @len) DO

INSERT INTO temp VALUES

(@wordcount, SUBSTRING(word, @counter, 1));

SET @counter = @counter + 1;

END WHILE;

SET @wordcount = @wordcount + 1;

END IF;

UNTIL done END REPEAT;

CLOSE cur1;

SELECT GROUP_CONCAT(letter ORDER BY letter SEPARATOR '')

FROM temp

GROUP BY id;

END$$

DELIMITER ;

CALL sort_letters();

MySQL

mysql> SELECT @@character_set_database, @@collation_database;

+--------------------------+----------------------+

| @@character_set_database | @@collation_database |

+--------------------------+----------------------+

| utf8mb4 | utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci |

+--------------------------+----------------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

mysql> CALL sort_letters();

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| GROUP_CONCAT(letter ORDER BY letter SEPARATOR '') |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| _-,;:!?.'"()[]{}@*/&#%`^+<=>|~$0123456789AaBbCcDdEeFfGgHhIiJjKkLlMmNnoOpPqQrRsStTuUvVwWxXyYzZ |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec)

PostgreSQL

Default collation for en-US locale:

blog=# select datname,datcollate from pg_database;

datname | datcollate

-----------+------------

postgres | en_US.utf8

blog | en_US.utf8

template1 | en_US.utf8

template0 | en_US.utf8

(4 rows)

WITH t(s) AS (VALUES ('!"#$%&''()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~'))

SELECT string_agg(substr(t.s, g.g, 1), ''

ORDER BY substr(t.s, g.g, 1)

) as char_order

FROM t

CROSS JOIN LATERAL generate_series(1, length(t.s)) g;

char_order

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

!"#%&'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\]^_`{|}~$0123456789aAbBcCdDeEfFgGhHiIjJkKlLmMnNoOpPqQrRsStTuUvVwWxXyYzZ

(1 row)

SQLite

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS demo;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS demo (s TEXT);

INSERT INTO demo VALUES

('!"#$%&''()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~');

WITH cte1(r,current,rest) AS (

SELECT rowid,substr(s,1,1), substr(s,2) FROM demo

UNION ALL

SELECT r,substr(rest,1,1),substr(rest,2)

FROM cte1

WHERE length(rest) > 0

LIMIT 255

),

cte2 AS (SELECT * FROM cte1 ORDER BY r,current)

SELECT r,group_concat(current,'') FROM cte2 GROUP BY r;

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS demo;

Output for the above SQL

!"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

We have publicly published semgrep rules for detecting potentially dangerous uses of the Django, Prisma, Beego, and Entity Framework ORMs at https://github.com/elttam/semgrep-rules to assist security testers and software developers.

It is important to note that these semgrep rules are not fully robust, due to limitations in semgrep itself and the inherent challenges of detecting vulnerable input parsing into ORMs.

For example, the following output from the django-orm-dynamic-lookup-variable-key rule did not detect the exact sink for Label Studio CVE-2023-47117, but it was able to identify that significant dangerous filtering logic existed within the file.

$ semgrep --config /rules/python/audit/orm-leak/django-orm.yaml /app/label-studio/

...

/app/label-studio/label_studio/data_manager/managers.py

❱ rules.python.audit.orm-leak.django-orm-dynamic-orderby-or-values

Dynamic field names used in order_by() or values(). Review if an attacker can influence the selected

or sorted fields.

161┆ queryset = queryset.order_by(f)

❱ rules.python.audit.orm-leak.django-orm-dynamic-lookup-variable-key <1>

Dynamic kwargs passed into Django ORM lookup methods with a variable key. Review if these keys can

be attacker-controlled (e.g. "user__password__contains"). This is a primary ORM Leak sink.

235┆ filter_expressions.append(Q(**{key: int(_filter.value)}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

238┆ filter_expressions.append(~Q(**{key: int(_filter.value)}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

242┆ filter_expressions.append(Q(**{key + '__isnull': value}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

359┆ q = Q(Q(**{field_name: None}) | Q(**{field_name + '__isnull': True}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

359┆ q = Q(Q(**{field_name: None}) | Q(**{field_name + '__isnull': True}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

361┆ q |= Q(**{field_name: ''})

⋮┆----------------------------------------

363┆ q = Q(**{field_name: [None]})

⋮┆----------------------------------------

366┆ q = Q(~Q(**{field_name: None}) & ~Q(**{field_name + '__isnull': True}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

366┆ q = Q(~Q(**{field_name: None}) & ~Q(**{field_name + '__isnull': True}))

⋮┆----------------------------------------

368┆ q &= ~Q(**{field_name: ''})

⋮┆----------------------------------------

370┆ q = ~Q(**{field_name: [None]})

⋮┆----------------------------------------

390┆ Q(

391┆ **{

392┆ f'{field_name}__gte': _filter.value.min,

393┆ f'{field_name}__lte': _filter.value.max,

394┆ }

395┆ ),

...

<1> The django-orm-dynamic-lookup-variable-key rule detected dangerous Django filtering in the apply_filter function, which was the root cause for Label Studio CVE-2023-47117.

The most effective approach we have found for identifying ORM Leak vulnerabilities is a hybrid of dynamic and static analysis: first identifying search and filtering functionality within an application dynamically, and then tracing the source code to uncover flaws in the query logic.

This will likely be our final article on the ORM Leak vulnerability class, unless we uncover a new exploitation technique targeting ORMs.

We want to emphasise that ORM Leak vulnerabilities do not depend on the use of susceptible ORMs such as Django or Prisma. Instead, this issue is widespread across modern web applications due to the growing demand for robust filtering capabilities. Developers often rely on the underlying ORM to provide sufficient validation, overlooking the fact that certain fields should never be queryable.

While SQL injection was once one of the most prevalent vulnerability classes, it is now relatively rare due to improved security awareness, training, and tooling. In contrast, we increasingly encounter applications that unintentionally allow users to search sensitive fields or control both the field and operator used in queries. As demonstrated throughout this series, these patterns can lead to significant data exposure.

We look forward to seeing further research into ORM Leak vulnerabilities and, of course, more cinematic proof-of-concept demonstrations of sensitive data being exfiltrated.

ORM Leaking More Than You Joined For

December 2025 - ORM Leaking More Than You Joined For

November 2025 - Gotchas in Email Parsing - Lessons From Jakarta Mail

March 2025 - New Method to Leverage Unsafe Reflection and Deserialisation to RCE on Rails

October 2024 - A Monocle on Chronicles

August 2024 - DUCTF 2024 ESPecially Secure Boot Writeup

July 2024 - plORMbing your Prisma ORM with Time-based Attacks

elttam is a globally recognised, independent information security company, renowned for our advanced technical security assessments.

Read more about our services at elttam.com

Connect with us on LinkedIn

Follow us at @elttam